Creativity was initiated with the very first step homo sapiens took on the surface of Earth. Ideas to create tools, food, shelter, and language evolved into the creation of civilization, writings, communities, and beliefs. When the human species moved from Africa and landed in India and its subcontinents, they encountered a land full of resources, opportunities, and benefit to attain livelihood. The thought of how the ancient inhabitants made arrangements for living and continuously were in process of progression is enchanting. People are not considered civilized unless they know how to write. The different forms of writings prevalent in India today are all derived from ancient scripts. This is also true for the language that we speak today. The language we use has roots in ancient times and has developed through the ages. Concluding, the words that we write and speak today came from the fingers of the early humans residing in the caves, where the art of hand prints signifies their identity and recites the story of their existence. Some formation of mutated figures of humans and animals suggests that they may have believed in extramundane powers and hence, it is never wrong to say that the actual potential to believe and create came from early humans in us.

The Indic or Indus culture is world famous for its town planning and ideas for smelting copper and tin to forge it into bronze, though not first, they gave us some fine artifacts to explain the dexterity of metallurgy. The seals and scriptures excavated exemplify their brilliance in creating a new language which is a collection of human and animal figures, innovative signs, and mythological characters. Not fond of paintings the Harappan people gave a major eye to sculptures and architecture. It is said that we have got the intelligence to build peculiar construction plans from the Indus civilization. Believing in powers that are way more compelling than human capacity is rooted in the culture of religion. Early or modern, humans are somehow connected to a force that makes them believe in customs, traditions, and religion. Art was the dominant way to carry forward the stories, platitudes, and epics in form of paintings, sculptures, scriptures, and architecture to the succeeding generations in ancient India.

Today we can see astonishing examples of Buddhist-influenced architecture and art mainly from the Mauryan Empire and Shunga dynasty to the late periods of the Kushan empire, sometimes Gupta and Pala eras, where not only Stupas, samba, Chaityas, and Viharas, but paintings and scripts were also added to the Indian patronage. Vakataka dynasty and Rashtrkutas further gave Buddhism a gleaming light by putting their contribution to the development of Ajanta and Ellora rock-cut caves and murals. Hindus and Jains also imitated the method of hewing caves to suit their purpose mainly at Badami, Aihole, Ellora, Elephanta, Aurangabad, and Mamallapuram under the patronage of Chaulakya, succeeding Rashtrakutas and Pallavas. The period under Gupta’s patronage fully deserves the name ‘the golden age’ of Indian art and culture as they added some magnificent architectural designs, majorly Hindu temples, and sculptures to Indian heritage. With the continuous evolution and progression of dynasties, architectural designs also got distinguished, mainly for temples, into Nagara styles in the Northern parts and Dravidian and Vesara styles in the southern parts of the country.

Indian art was advancing at a good pace with diverse influences from numerous regions, i.e., Rajasthan in the West to Odisha in the East, from Kashmir in the North to Tamil Nadu in the south, when the Indo-Islamic culture stepped into Indian lands, carrying a totally new style of art and architecture and hence a mutation was born, with the name Mughal art. Mughal art and architecture soon spread widely, especially during the period of Akbar and Shahjahan. Earlier Indian dynasties never focused much on paintings but on carvings and cuttings, after the Mughal's arrival, Indian paintings got an elevation, showcasing the miniature style of works, being merged with Rajasthani, Rajput, and Pahari styles of miniatures. Soon after the boon of Indo-Islamic culture, the Europeans came into the lands. The East India Company, though fascinated by Indian art favored their European appeal of works. They rooted many art schools to indulge a European allure to Indian art and to satisfy their artistic desires. Indians soon adapted their former cultural themes with a new blend of style stepping aside the European admirers, hence giving birth to the modern and contemporary forms of art. Though culture and heritage have always played a central role in Indian art, the techniques and styles kept on evolving from generation to generation. The prints laid by early humans have always been in our DNA, the Influence of which can be seen in the form of language, visual arts, performing arts, religious or cultural arts, and in ourselves as well.

Text by

Sanchita Sharma@Art Blogazine

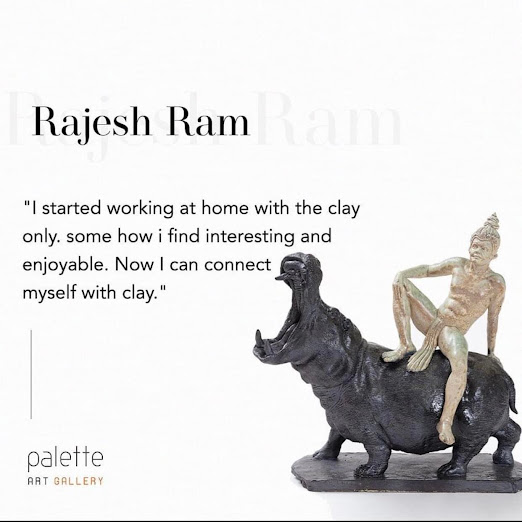

1 Image: BULL during various periods and times. Bhimbetka caves, Indus valley, Maurya era, Shunga dynasty, Ajanta caves, Chandella dynasty, Nandalal Bose, M.F. Hussain, Subodh Gupta.

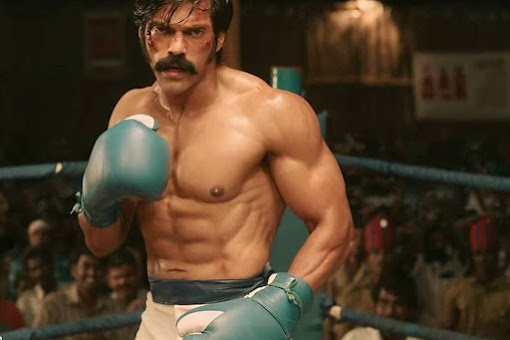

2 image http://jameelcentre.ashmolean.org/object/LI118.86, Source: google/image / no copyright image fron art blogazine